You Can't Go Dome Again

On the 25th anniversary of the last Mariners game at the Kingdome, I remember growing up in that beautiful ugly Dome.

I loved the Kingdome.

I loved the walk through Pioneer Square to the edge of the parking lot, the ‘Dome looming at the end of it. I loved walking up those endless ramps on the exterior, seeing more of the city the higher you went. I loved the first glimpse of the orange seats through the hazy lighting, the dull gray of the ceiling contrasting with the artificial brightness.

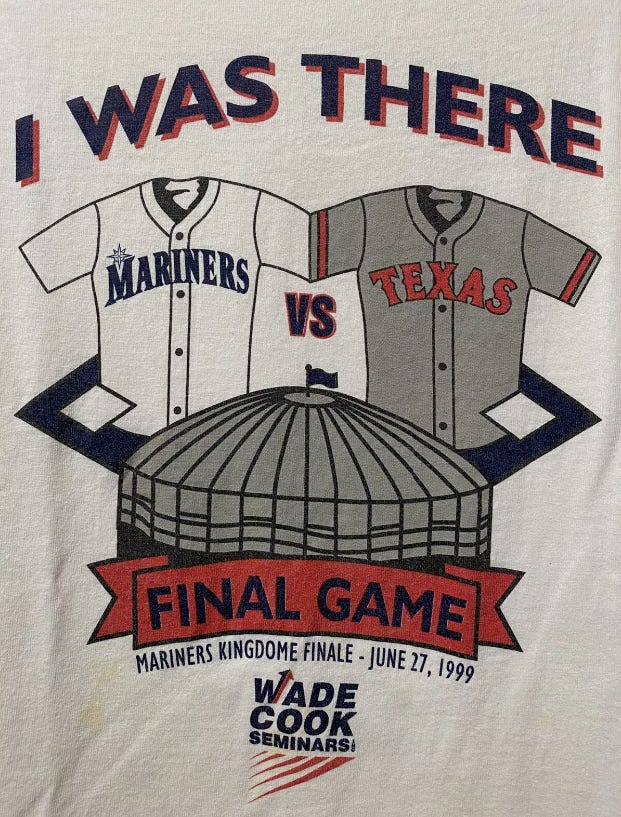

The Kingdome hosted a few years of good baseball, and a couple decades of very, very bad baseball. And 25 years ago today, the Mariners played their last game there.

I wrote about the game itself, and many of the things I loved about the Kingdome, for the 20th anniversary of the last game, which you can read if you’re so inclined: https://www.lookoutlanding.com/2019/6/27/18710949/the-last-game-at-the-kingdome-a-baseball-love-story

As I was thinking about the last game and reminiscing about the ‘Dome this week, I realized it wasn’t the baseball I saw there that made me love it so much. It was the life that happened while I was watching baseball there. It’s a place where I grew up, and going to games at the Kingdome is a coming of age story for me.

****

I saw my first baseball game at the Kingdome, sometime in the mid-1980s. I fell in unconditional love with baseball at the Kingdome during an extra inning game in 1990:

As I got older, it was a place I cemented a bond with my dad even as I pulled away from my parents during my teenage years. It was a place I dragged my friends, where we existed in that liminal teenage space of independence and dependence, no longer children but not quite adults

The first game I remember going to with my friends was the last game of the 1997 season, a Sunday afternoon loss to Oakland. My friend’s dad drove us to the game in the Chevrolet G20 van he often carted us around in (it was the most luxurious of all our parents’ vehicles). I arrived at her house to find another of our friends aglow with a new baseball crush. She’d watched Raul Ibañez hit the first home run of his career the night before and she was in love. It was the beginning of years of hearing about him. At one point she wrote me a letter that was just a sheet of notebook paper covered with Raul, written hundreds of times.

Teenage girls drive pop culture. It wasn’t adult men screaming for the Beatles on the Ed Sullivan Show, you know. Yet, the things teenage girls like are disparaged and their tastes and life experiences are disregarded (something that continues well into adulthood, I would learn). I listened to a lot of sports radio in those days and the message came across the radio waves very clearly: it was not cool to be a girl, nor was it cool to like the things that girls liked.

My rabid baseball fandom was likewise dismissed by people of all genders. Oh, they’d tell me, you just think the players are hot. I hated hearing that this thing I loved in so many different ways could be boiled down to a single point. I felt the need to pretend that I did not, in fact, think the players were hot. I wanted to be taken seriously as a real baseball fan, not a silly, frivolous girl baseball fan.

Part of the joy of going to games with my friends was not needing to hide the fact that, yes, part of what I enjoyed about baseball was the hot players. How can you not? It’s a great sport to get into if you’re attracted to men! We spent a lot of time in the Kingdome bleachers discussing the players. Who was hot. Who we thought would be a jerk. We plotted ways we could convince Mariners players to go to Prom with us. We went into details about the things we thought about them, details I will not share here. (You’re welcome!) People like to talk about the lustiness of teenage boys; I’ll just say if you think that is noteworthy you have clearly never been, nor been around, a teenage girl.

One game, we arrived early to find the teams weren’t taking batting practice. Mike Sweeney had been out catching a bullpen and came over to us in the stands. After signing some things, he talked to us for a while. He talked some good-natured trash about the Mariners, and forever endeared himself to me, the person who was ecstatic when he became a Mariner.

At another game, we put our ticket stubs and a pen in a binoculars case with a note asking players to sign them, and threw the case over the dugout, attached to shoelaces and hoodie strings. After a bit, we felt a tug on the string and pulled the case back up. Inside was a baseball and several pieces of bubble gum. I kept that gum for years, until my brother took it and chewed it. (Yes, I’m still mad!)

My 10th grade English teacher, himself a baseball fan and season ticket holder, often let us use his tickets when he couldn’t go to a game. We’d spend our lunch breaks in his classroom, making huge signs with rolls of butcher paper. One memorable day during batting practice, we held up signs as we stood along the third base line, screaming at the players. They threw a lot of balls our way…in between pointing and laughing at us. It was an amazing day.

We sat in the cheapest seats one afternoon game next to an old woman with her scorebook and knitting. She had something positive to say about every player and I decided I wanted to be her when I grew up.

We often tried to move down into the nicer seats as the game went on, and often were sent back where we came from. One day, my friend and I found a pair of tickets on the ground in the 100-level concourse. The seats were a few rows behind the visiting dugout. No one was in the seats; it was a huge victory. We obviously didn’t belong there, but no one could make us leave because we had tickets.

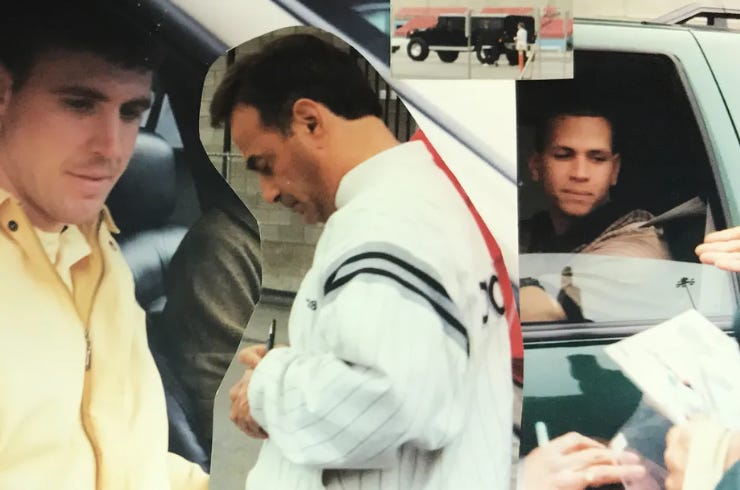

It was easier to get close to the players and get autographs at the Kingdome than it was later at Safeco Field. We’d hang out after the games for hours, waiting for the players to drive out from the bowels of the Dome. Sometimes they’d stop and sign, sometimes they’d just wave and drive off. Either way, it was a thrill.

I got Ryan Franklin’s autograph on my ticket stub the night of his major league debut, after which he drove away in a clunky brown car that I imagine he replaced after getting a major league paycheck. I waved to Jay Buhner, driving away in his Hummer. I listened to a group of women who were probably in their 30s talk about Russ Davis being a good Southern boy in ways that put my own innocent crush on him and the discussions with my friends in the bleachers to shame.

Visiting teams became accessible near the end of the Kingdome. Their busses would pull up outside the ‘Dome and we could gather along barricades and ask them for autographs. One of my friends decided she didn’t want autographs; she would ask the players for a hug instead. We were probably 16 at the time. I remember gathering next to the visiting Royals’ bus when Jeff Suppan walked out and my friend asked him for a hug. He looked back and forth between us a couple times and said, “Umm, you guys look really young. How about I give you a handshake?” She happily accepted, and from then on asked players for handshakes.

While we’d wait outside for the players to come out, boys would try to flirt with us. Most would brag about how many autographs they had, as though that held any sort of currency with us. When all the players had left, we’d call one of our parents from a pay phone outside the box office, dialing 1-800-COLLECT, and yelling “We’re ready to be picked up!” into the phone when it asked for our name, then hanging up, somehow trusting the message would get through.

Sometimes we’d lug in our backpacks and do homework in the stands during batting practice. We obtained driver’s licenses and began driving ourselves to games. We had silly conversations about the players and about the latest drama at school and the boys we knew. We had serious baseball conversations and debated Lou Piniella’s bullpen usage. We treasured those hours, running free around the Kingdome. Away from our parents. Away from school. A place we could be ourselves, in all our changing, teenage dimensions.

*****

I went to the last game at the Kingdome with my dad. For all my branching out to games with my friends, that’s who I wanted to be with at the last game there. It was a solemn experience going in. I was excited for the new stadium, because I was supposed to be. But I was sad to say goodbye to a meaningful piece of my childhood. I was 17 then, and had just finished my junior year of high school. It was a harbinger of the year to come, when I’d decide on a college and graduate high school and move across the country by myself, jumping feet first into being a grownup.

The last game was a joyful, a celebration rather than a funeral. Ken Griffey Jr. had a classic Ken Griffey Jr. game. He hit a home run with cameras flashing. He robbed a home run with a catch that looked deceptively easy. Freddy Garcia threw his beautiful curveball, giving us a flash of things to come. It was a muddle of endings and beginnings, of saying goodbye and hello.

A year later, I turned 18 and had friends over to my house for a sleepover. We talked about college and jobs and graduating. We did each other’s hair and makeup. We talked about the last few months of high school. In the morning, we woke up to watch the Kingdome implode.

Ready or not, the ‘Dome was gone, and the people we had been there were already someone else.

The Actual Last Baseball Game at the Kingdome

Although the game on June 27, 1999 was the last Mariners game at the Kingdome, it wasn’t the last baseball game there. That distinction belongs to an amateur league that held a tournament there the following spring. I learned about this from a comment on my Lookout Landing article. Commenter Greg Cole wrote:

The Eastside Pirates won the championship game in the "Kingdome’s Last Stand" tournament, which was a tourney held by National Adult Baseball Association, one week prior to the start of the tear down of the Kingdome. Steve Towey hit a 380 foot home run, which was the real last home run hit there….just for history buffs.1

The Best Song Written About the Kingdome

Obviously that distinction belongs to former Mariner Lenny Randle and the Ballplayers (also Mariners). The song came into existence during the 1981 strike and was released in 1982. It’s an absolute travesty that this song was not played at every single game in the Kindome:

I’d love to link to this, but SB Nation redid their comment system in favor of something that is much worse and it wiped out all the old comments. I’m forever grateful I grabbed screenshots of my comments before that happened. They are full of little gems like that.