When the Mariners Owned the Padres... *Almost* Literally

Today we explore an incident in the Mariners-Padres rivalry that's really something. Maybe the real Vedder Cup was the teams we tried to buy along the way.

But first, fun news! I will be presenting at the SABR Women in Baseball Conference on September 21st about the Women of the Portland Mavericks. Anything to do with the Mavericks is a good time, and this story is an interesting snapshot of the confluence of second wave feminism and sports, and a time when it seemed like things were rapidly changing.

Today, the Mariners are wrapping up the season series with their “geographic rivals”, the San Diego Padres. For years we’ve made jokes about this being a manufactured rivalry, but what if there is some truth to the Mariners and Padres as natural foes? Today, I dig into one incident in a surprising history of incidents between the two teams, long before interleague play was even a gleam in Bud Selig’s eye.

The year is 1987. Ronald Reagan is President, inflation is rampant, and Mariners owner George Argyros is tired of his team.

So, he did what any blustering millionaire would do. Then, he called his manager.

“I have some good news and some bad news.”

“Just tell me everything,” Dick Williams replied on the morning of March 26.

“I’m going to buy the Padres and I’m putting the Mariners up for sale.”1

And thus began a strange two months in Mariners history, the culmination of an incoherent six years.

*****

Dick Williams was the Mariners’ 6th manager in 10 seasons. He was hired in May 1986 to turn the team around, but the then 20-loss team tacked on another 75. In half their seasons of existence, the Mariners had finished with 95 losses or more.

They were an attractive team to a manager who wanted credit for a turnaround, and Williams was known for just that. The Mariners had a number of promising young players including Alvin Davis, Spike Owen, Jim Presley, and Mark Langston. Williams carried a reputation for being old school and was often condescending and sarcastic to his players, with no praise or pats on the back to soften the blows. So, heading into 1987 the Mariners had flashes of talent, hints of a brighter future, and no support to get them there.

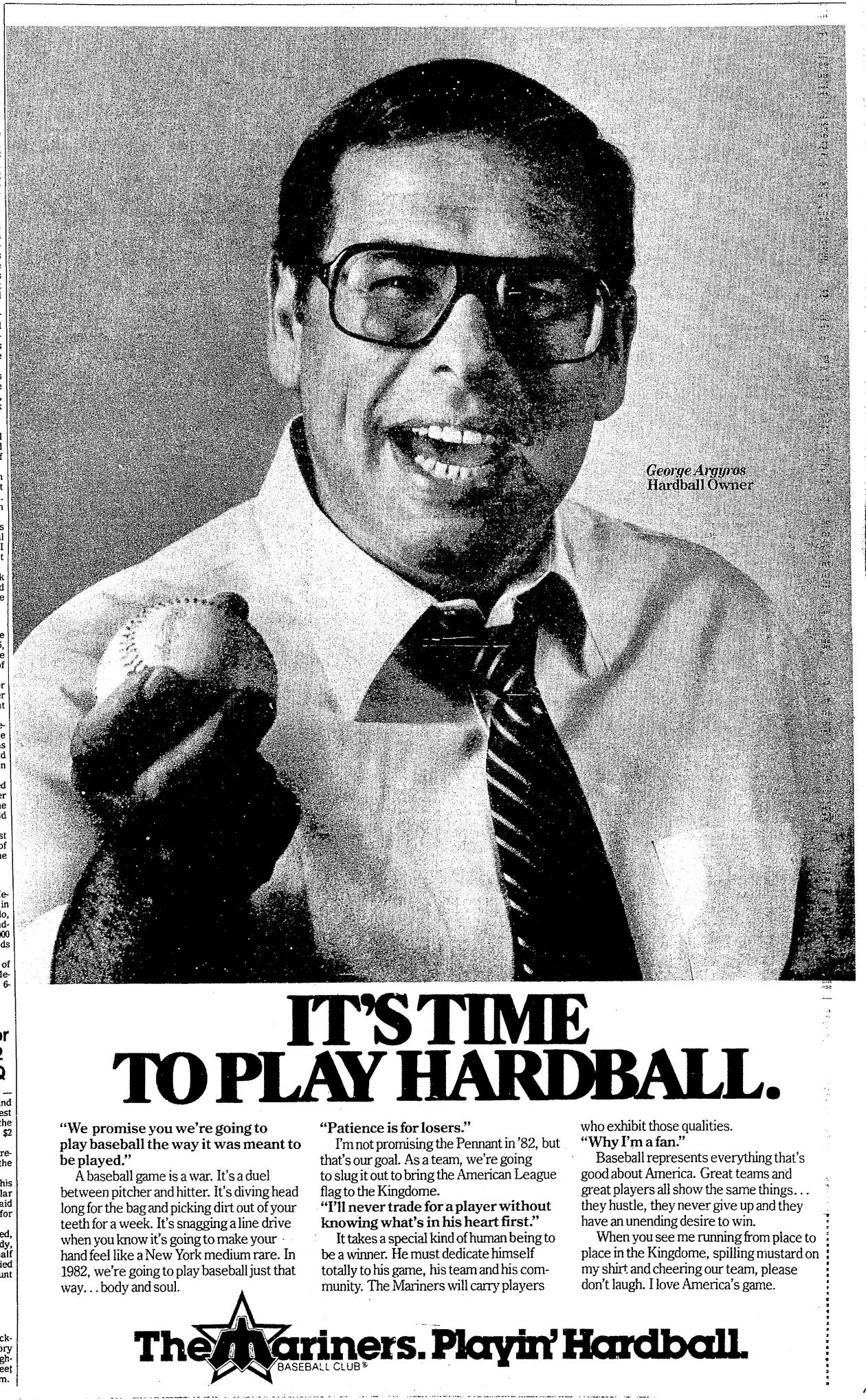

The parade of managers through the Kingdome in the first decade certainly bore the public-facing blame for the team’s perpetually poor performance. But no one was the cause more than the man who owned the team. George Argyros purchased the Mariners in early 1981. Like the original ownership group before him, he quickly learned that owning a baseball team was an entirely different beast than any other business.

Argyros lived his life with one mission: making himself a fortune. He identified insurance, securities, and real estate as the best industries to make a lot of money and “I got my licenses in all three in 1962,” he said in a 1985 profile that originally ran in the Orange County Register.2 A year later, he was planning his first subdivision. He made much of his fortune building and retaining apartment buildings in Orange County, CA. Newspaper stories of his real estate ventures are plagued with anecdotes about aggressive rent collection, illegal fees, and stinginess over security deposits.

He earned widespread admiration in the business world as a self-made millionaire. He constantly extolled the virtues of capitalism in the United States; he was the son of Greek immigrants and believed he could not have been successful in Greece.3 When you’re enamored with Americana and have millions of dollars, what can you do but buy a baseball team?

Argyros loudly barged into Seattle and baseball. His quotes in the newspapers at the beginning of his reign are perfect fodder for “Cold Takes” and “Images that Proceed Unfortunate Events” social media accounts. The Seattle Times sports editor, Georg N. Meyers noted that Argyros “with no tongue visible in cheek, said he ventured into baseball, as an adjunct to his business as a real-estate developer to improve his image”, feeling like the coverage of his real estate dealings were unfair.4

Argyros shared a quotable piece of advice he handed to MLB Commissioner Bowie Kuhn during a Spring Training conversation, a quote that would haunt him for the rest of his time in Seattle:

“Patience is for losers.”

If baseball was America’s favorite game, fighting with King County over the Kingdome lease was Argyros’s favorite game. He claimed the lease made it impossible for him to field a competitive team and make money, and threatened to move the team in order to get a better deal as early as 1984.

Despite talking about winning and making fans happy, Argyros was never willing to invest in the team. He let free agents walk, he lowered payroll, he suggested they simply try harder and embrace the power of positive thinking. But he never gave them the tools, the personnel, or the financial incentive to be better.

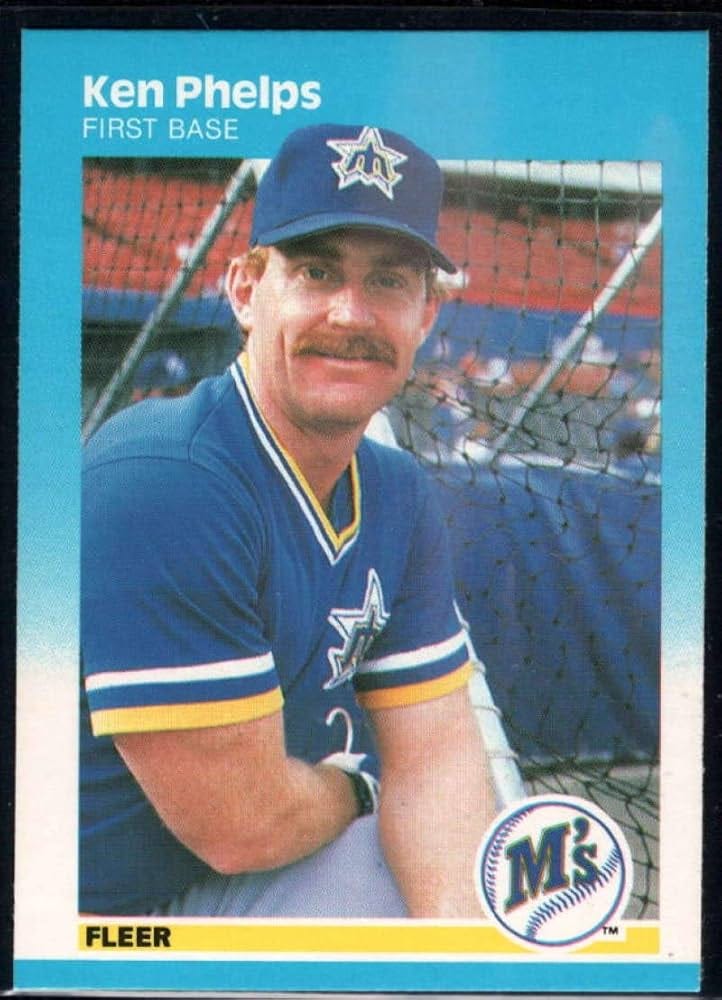

First baseman Ken Phelps is known for his trade to the Yankees for Jay Buhner (which famously angered Frank Costanza) in 1988. But he also deserves to be remembered for not being shy about ripping Argyros in the local papers. Comments that eventually made their way into a brutal Sports Illustrated article about the team in 1988 seem to have originated in a Steve Kelley column in the Seattle Times. Phelps didn’t hold back his opinions about the owner:

You wonder how much the Mariners really want to win…It would be nice if, just once, the Mariners would take a chance and spend a little money.

…Players don't want to live in Seattle in the off-season because they never know if they're going to be here long. The Mariners have a history of getting rid of good players. It's sad to think that nobody wants to live here. It's hard to establish a rapport with the fans.

I love Seattle. I want to see baseball succeed here. But in the back of my mind I wonder if they don't draw this year are they just going to leave town? The trades they made kind of make you wonder. If I were a fan, I would think, ‘Why bother buying season tickets when the team is filled with no-names and rookies?’

…If you're going to pinch pennies, you shouldn't be in the business. You can't run a business like that. The Mariners have never played .500 ball in their history. That should tell you something about this franchise. Believe me, all the players talk about it. And they talk about the fact that the salaries here are so low.

I think, ideally, owner George Argyros would like to have about a .500 club and also have the lowest payroll in baseball. If he got lucky and won, that would be frosting on the cake.”5

Unsurprisingly, attendance suffered. After attracting a franchise-low 814,000 fans for the 1983 season, Argyros expressed frustrating at losing $6 million that year and blamed the fans and the county:

Every city that considers itself major league would like a major league baseball team. You know, there are only 26 major league baseball cities in the world and obviously it’s an important commodity.

…if the fans don’t turn out and the Kingdome doesn’t help with that situation…we’ll look at all the alternatives and that includes moving to another city.6

Chuck Armstrong was hired as club President in 1983 and spent much of his early tenure walking back and clarifying things Argyros spouted to the press. He said some of the problem the Mariners were having was that Argyros was too involved in advertising for the club. Never mind that Argyros himself wanted to use the team to improve his image. Armstrong assessed that, “Some misguided public-relations or advertising people convinced George he ought to become the Lee Iacocca of baseball.”7

Armstrong also poopooed talk of bankruptcy:

The bankruptcy business is always there with every business. We never mention it because it is a threat. We don’t want to get support by threat. We want support because people like us.

…For us, it’s business as usual, if the community gives us a chance now.8

For all his pleading for fans to attend Mariners games, Argyros did everything in his power to alienate the fan base. He demanded to renegotiate the Kingdome lease with King County in 1985. The county warned that providing too many financial concessions to the Mariners would plunge the Kingdome into debt and cost taxpayers money. Argyros claimed he could not run a baseball team under the current lease. The Mariners agreed to mediation with King County in June 1985 and a new 12-year lease was agreed upon. Argyros got one concession he desperately wanted; the Mariners could leave town after 1987. If the Mariners pulled in an average attendance of at least 2.8 million over a two-year period or had season ticket sales averaging over 20,000 they would have to stay. In return, Argyros had to invest at least $7 million into the team.9

Surely, you can see the issue here. The mediators took Argyros at his word that he wanted to build a successful baseball team in Seattle. But what if he didn’t? After all, the exit clause was a huge sticking point for him. And Argyros’ home and other businesses were all in Orange County. But the idea of moving the Mariners to Southern California was ridiculous. With the Angles, Dodgers, and Padres already in that half of the state, there wasn’t room for another team.

The exit clause would make the team attractive to another buyer, however. And that came into play in 1986 when the Padres went up for sale.

*****

The Padres. Where do we start with the Padres?

The Padres were a hot mess.

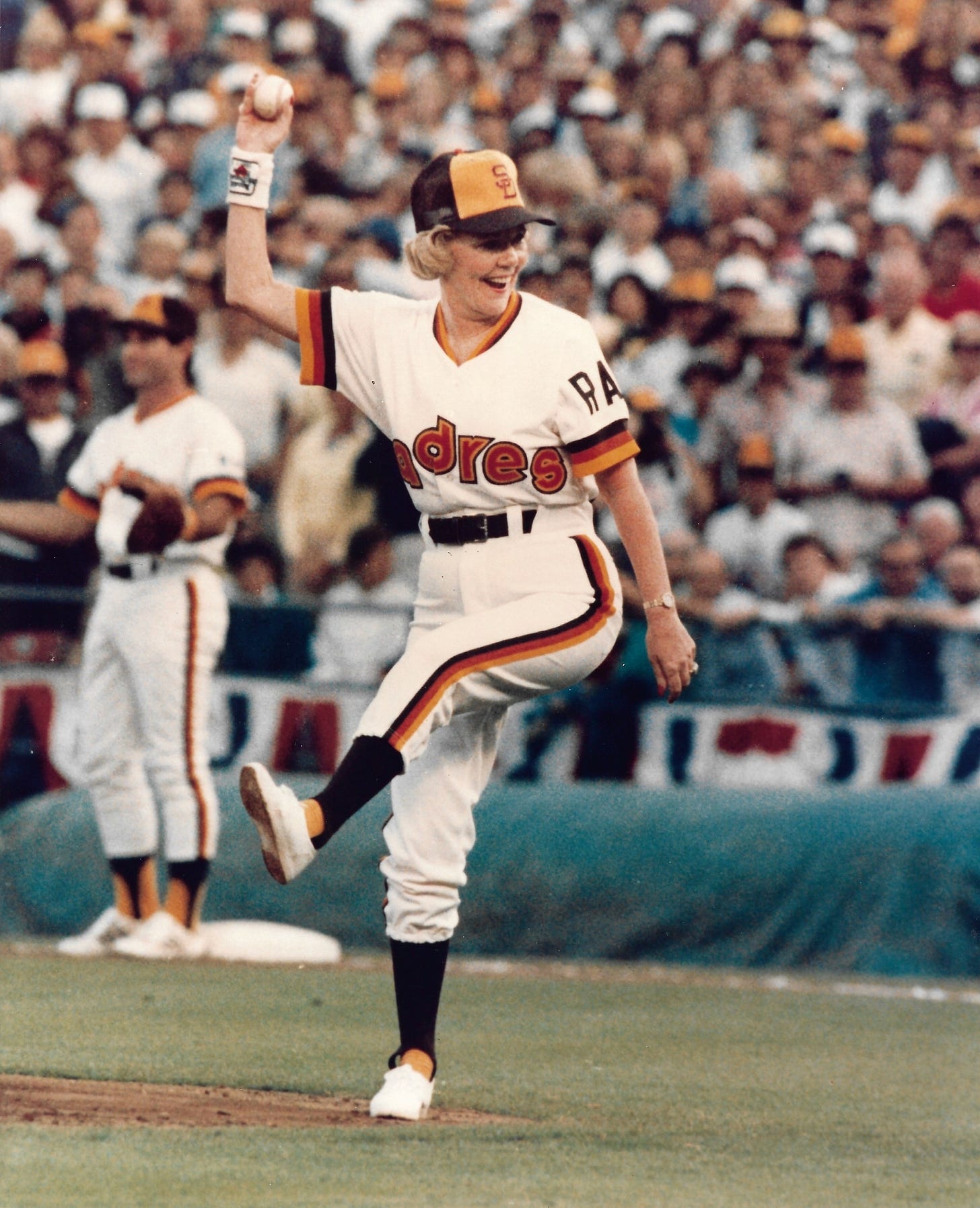

Joan Kroc owned the team; she inherited it in 1984 upon the death of her husband, Ray Kroc, the founder of McDonalds. Dick Williams was hired in 1982 to turn around a 41-69 season (shortened due to the strike in 1981). He was successful; in 1984 the Padres played in the World Series for the first time. But the ‘84 team was a high mark for the club. Injuries threw the team off course in 1985 and the team all but collapsed in 1986 due to player substance use problems and conflicts between players and management.

In May, Kroc first expressed her intent to sell the Padres. Steve Garvey, then the Padres’ first baseman, was interested in putting together an ownership group for the $50 million price tag. Garvey was unsuccessful, and in November Kroc announced that the team was officially open to offers.

*****

The Mariners needed to sell 2.8 million tickets or 20,000 season tickets over the course of the 1986 and 1987 seasons for Argyros to keep them in Seattle. At the end of 1986, they were about 350,000 short of the 1.4 million halfway mark, meaning they would need to sell at least 1.75 million tickets in 1987 (an average of over 20,000 a game; they averaged less than 13,000 in 1986). If the team was short on its sales figures, King County and the City of Seattle had the option to pay the difference and keep the team in town.

Argyros talked all offseason about blockbuster trades and free agent signings, but as spring training neared its end the Mariners had done nothing to make a splash.

With all the uncertainty in the air the Mariners’ marketing department had a brilliant idea for the team’s 1987 slogan: Playing for Keeps.

*****

The question of the Mariners staying or going suddenly became more pressing on the morning of March 26 when Joan Kroc announced she had accepted George Argyros’s offer to buy the Padres.

“It is with a sense of sadness that I must give up something that I have loved so much and worked so hard to develop these past six years,” Argyros disingenuously said at his press conference announcing that he was putting the Mariners up for sale.10 He hoped to take over the Padres within 90 days.

The news was a shock to everyone. For all the threats about moving the Mariners, there hadn’t been any indication that Argyros would sell the team. A Mariners club source told the San Diego Union Tribune that the purchase of the Padres and sale of the Mariners “was completely out of the blue. Periodically, he would mention that he was disenchanted with the M’s and the county. He would threaten to move the club. But he never suggested seriously that he wanted out.”11

Major League Baseball rules prohibited ownership of more than one club so the race was on to find a local buyer. President Chuck Armstrong said he was interested in putting together an ownership group, but he didn’t think he had enough time. That sort of process generally took 6-9 months and a buyer was needed much sooner.

Shortly after the 1987 season was underway, Baseball Commissioner Peter Ueberroth ordered Argyros to remove himself from the operations of the club. Armstrong took over, running the team on his own, and Argyros was allowed one phone call a day to approve big decisions. MLB and the National and American Leagues were in an unprecedented situation and were adamant about avoiding even the appearance of a conflict of interest.

After the Padres beat the Dodgers in extra innings in an early season game, Argyros took it upon himself to give Padres manager Larry Bowa a ring to congratulate him on the win. When Bowa took the call, the National League president, A. Bartlett Giamatti, just happened to be in his office. Giamatti reported the incident to Ueberroth. Ueberroth scolded and fined Argyros $10,000 for the phone call, and told him that he needed to stay out of the Padres’ business; he did not own the team yet.

Ueberroth iterated over and over that MLB only wanted a local buyer for the Mariners. It was the number one criteria when it came time to approve the sale, he said. Ueberroth went on to gush about what an incredible asset the Mariners were; no lawsuits, no long-term contracts. A payroll that was the lowest in baseball for the third year in a row.12

Argyros was, after all, a businessman. Buy an asset, tank it, reap the benefits after you drive it into the ground.

*****

In late April, doubts began to sprout about whether Argyros’s purchase of the Padres would be approved. Carl Barger, the Pittsburg Pirates’ secretary and general counsel said of Argyros, “What he did—to own one ballclub and agree to purchase another ballclub—is highly unusual. One could call it almost bizarre. There was no intervening process like you normally have. I just think he’s…I guess the word is controversial.”13

The National League owners were scheduled to meet on June 11 and vote on the acquisition. Just four “no” votes would kill the sale. That one team was speaking publicly about their hesitancy to support to sale wasn’t a good sign for ole George.

In other twist that screamed “conflict of interest”, Steve Garvey—remember, an active San Diego Padres player and a member of the group that had tried to buy the Padres—said he had a group that was interested in buying the Mariners and keeping them in Seattle. At the same time, Argyros was quoted in the Los Angeles Times saying he’d like have Garvey in the front office for the Padres.14 Giamatti was furious over the remark. Argyros had repeatedly been asked to keep his mouth shut, but he continued doing just as he pleased. Surely pissing off the president of the league from which you need approval to buy a team wasn’t the best strategy.

In mid-May Argyros rejected an offer for the Mariners by Bruce Engel of Portland, who is described alternately as a lumber baron and a lumber tycoon. No real reason was given, simply that they couldn’t reach an agreement. Seattle developer David Sabey made on offer on the club in late May, but Argyros said there was nothing to discuss.

In May, the Mariners were preparing for the upcoming amateur draft. Because they finished last in the American League in 1986, they had the first pick in the draft. The consensus number one pick was the son of major league outfielder Ken Griffey. Everyone in the Mariners organization wanted Ken Griffey Jr. Everyone that is, except for their owner. Argyros was adamant that he wanted the Mariners to draft college pitcher Mike Harkey.

It would be easy to argue that he didn’t care all that much who the Mariners drafted when he was in process of selling them, but as the front office tried to convince him to take Griffey instead, the draft negotiations suddenly took on more urgency.

Five days before the draft, on May 29th, Joan Kroc announced she would not sell the Padres that season. She said of the decision not to sell:

I think when we signed the deal we both figured it would be relatively simple, uncomplicated and able to be completed by June 10, when the National League meeting is. George and I had a meeting last Tuesday and it became quite clear that neither of our goals could be accomplished by that time.

I feel strongly that it is not fair to the community in either Seattle or here to keep things in limbo. So we made a joint decision, very cordial, that we would just discontinue negotiations. We ran out of time. The clock ran out.15

Argyros said at his own press conference, “Sometimes the best deals are the deals that are never made.”16

It’s hard to say that was true for the Mariners on the field. They were off to the best start in their history since Argyros announced they were for sale. They were 23-23, 3rd in the American League West and only 4.5 games out of first.

After all of the hullaballoo, the Mariners were back where they started in Spring Training, worrying about ticket sales and whether the team would leave town.

******

Kroc held on to the Padres until 1990. Whatever else can be said about her time as owner, she was steadfastly dedicated to keeping the Padres in San Diego and publicly expressed appreciation for the fans, seemingly having a sense of the public trust she held as an owner of a major league baseball team.

When she put the team up for sale after the 1989 season, she said she was looking for “a high class, genuine, no-tight-purse-strings owner. I’m never going through the agony of the George Argyros sale again…Only quality people of integrity need apply. I’m not wasting time with an owner I wouldn’t want as a fan.”17

*****

Argyros spent the remainder of the 1987 season countering claims in the press that he wouldn’t have been approved by NL owners. He lobbed shots at Kroc. He feuded with the King County council over the Kingdome lease. Argyros bought the Mariners in part to rehab his reputation in the press. Instead, he become a baseball owner no one wanted to deal with.

The 1987 Mariners finished with the best record in their history, 78-84 in 4th place in the American League West. And, they drew 1,134,000 fans, the highest attendance since their inaugural season.

They stayed in Seattle with George Argyros until 1989 when a sale was completed to hand the team over to Jeff Smulyan who……you know what, we don’t need to get into that today. Argyros never owned another baseball team, but he was named Ambassador to Spain by President George W. Bush and his net worth suffered no repercussions from being bad at baseball team owning.

Most significantly, the rest of the Mariners front office and scouts finally convinced Argyros that the right move was to draft Ken Griffey Jr., which was a significant element in keeping the Mariners permanently in Seattle.

As the Mariners wrap up the 2024 Vedder Cup with the Padres today, let’s be grateful that terrible ownership is a thing of the Mariners’ past.

Huh.

Well, maybe someday.

FINNIGAN, BOB. "`IT'S GOING TO BE INTERESTING' - WILLIAMS." THE SEATTLE TIMES, March 26, 1987: H2.

IMSE, ANN. "WINNING IS HIS BUSINESSWHETHER THE GAME IS REAL ESTATE OR BASEBALL, ARGYROS DOESN'T LIKE TO LOSE." THE SEATTLE TIMES, June 30, 1985: C1.

IMSE, ANN. "WINNING IS HIS BUSINESSWHETHER THE GAME IS REAL ESTATE OR BASEBALL, ARGYROS DOESN'T LIKE TO LOSE." THE SEATTLE TIMES, June 30, 1985: C1.

Meyers, Georg N. “M’s owner’s goal: ‘Good seat hardest thing to buy in Seattle’.” The Seattle Times, April, 9, 1981: C1.

Kelley, Steve. “Phelps Ready with Rhetoric for Arbitration.” The Seattle Times, February 2, 1987: D7.

Cour, Jim. “Argyros wants to stay, but…”. The Seattle Times, June 21, 1984: B2.

Smith, Craig. “Suit, Olympics keep M’s attendance down.” The Seattle Times, August 24, 1984: E3.

STAFF REPORTER, BOB FINNIGANTIMES. "M'S BANKRUPTCY NOT DISCUSSED YET, DESPITE LOSSES." THE SEATTLE TIMES, February 3, 1985: C1.

SMITHTIMES STAFF REPORTERS, JACK BROOMCRAIG. "M'S WIN EXIT CLAUSE IN NEW LEASEAGREEMENT COULD LET M'S LEAVE TOWN AFTER '87." THE SEATTLE TIMES, June 25, 1985: A1.

and Nick Canepa, Barry Bloom. "Kroc accepts offer to sell the PadresSeattle owner to keep team in San Diego." Evening Tribune (San Diego, CA), March 26, 1987: A-1.

Slocum, Bob. "Who is George Argyros?New Padres owner successful in business but not in baseball." Evening Tribune (San Diego, CA), March 27, 1987: E-1.

P-I Reporter, Art Thiel. "M'S REINS HANDED TO ARMSTRONGUEBERROTH PUTS CLUB PRESIDENT IN CHARGE." Seattle Post-Intelligencer, April 11, 1987: B2

P-I Reporter, Art Thiel. "ARGYROS DEAL FOR PADRES MAY HIT SNAGLEAGUE APPROVAL IS IN DOUBT, A PIRATES EXECUTIVE SUGGESTS." Seattle Post-Intelligencer, April 25, 1987: A1.

Collier, Phil. "Giamatti: Argyros sport's James Watt." San Diego Union, The (CA), April 27, 1987: C-1

Bloom, Barry. "Padres sale offKroc keeps team." Evening Tribune (San Diego, CA), May 29, 1987: A-1.

NALDERROBERT T. NELSONDAVID SCHAEFER, TERRY MCDERMOTTERIC. "ARGYROS WILL KEEP MARINERSHE WILL SEEK LOCAL INVESTORS TO BUY 20 PERCENT OF TEAM." THE SEATTLE TIMES, May 29, 1987: A1.

Davis, Rick. "Padres for saleLakers' Buss listed among possible buyers." Evening Tribune (San Diego, CA), October 18, 1989: E-1.

This was fascinating. I thought I knew a lot of baseball. I didn’t know any of this. Just wow. Bravo for this retrospective piece.

I’m glad I was too young to care/notice during those days. Sounds terrifying