Internet Fandom and the Seattle Mariners, Part 1: Email Lists and the World Wide Web

The Mariners were the first professional sports team to jump on the information superhighway (remember when we called it that?!). But Mariner fans had already staked a claim in cyberspace.

The internet as a place is in a state of flux right now. Search engines don’t work as well as they used to, Twitter is…whatever it is, and Congress is focusing on important work like banning Tik Tok. As all of this happens, it’s made me a little nostalgic for the old days of the internet.

There was, of course, Mariners Twitter. There were pioneering sabermetric blogs. The comment sections of blogs became virtual gathering places for fans and built communities. Fan blogs, where anyone could pretend to be a sportswriter, and sometimes, turn themselves into one, popped up all over the place. The evolution of the internet as a place for fans to gather has been a huge part of Mariners history, and both the team and its fans have led the way.

This is the beginning of an occasional series looking at different aspects of the developments on Al Gore’s internet and online Mariners fandom along with it.

Seattle in the 1990s was associated with a handful of things. There was the rain. “It rains nine months of the year in Seattle,” Niles Crane tells Meg Ryan in Sleepless in Seattle. There was the coffee. “…judging by the caffeine consumption, Northwesterners are…wired as tight as Madonna’s bustier,” the Los Angeles Times wrote with the awe of discovering a new subculture. There was Boeing and grunge, and a local guy with a little business called Microsoft.

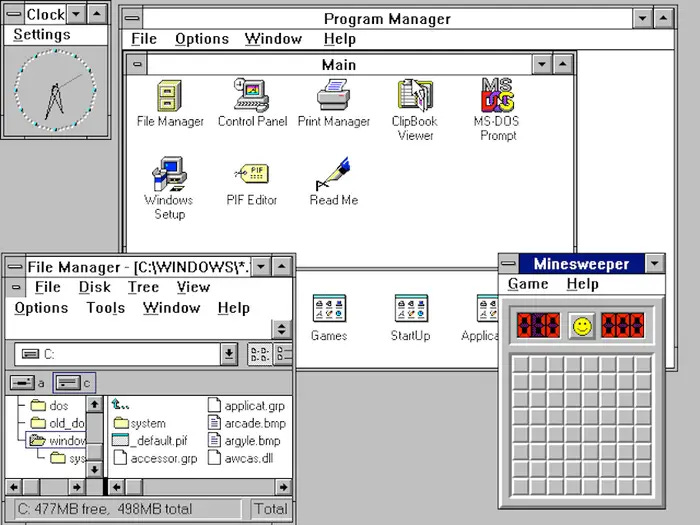

Early in the decade, we were typing our little commands into MS-DOS and peeling the sides off printer paper. Those of us in the in-between generation of Geriatric Millennials/Xennials were in the computer labs at school playing Oregon Trail. Personal computers were weaseling their way into our every day lives and as the home base for Microsoft and the home town of Bill Gates, it felt like we were right in the middle of it all. The other side of tech in those early days was video games. Locally-based Nintendo of America bought the Mariners in 1992.

Playing in Microsoft’s backyard and being owned by a major video game company, it’s no surprise that the Mariners became the first professional sports team with a website. At the end of November 1994, the Mariners Home Plate hit the internet.

*****

The internet had been around for a good 25 years by the time the Mariners joined. It grew from a network the Department of Defense set up so that government work could continue if we were all nuked. It slowly expanded and more entities joined, including universities and governments around the world. Although Al Gore never actually claimed to have invented the internet, he did play a huge role in making it more accessible for the average person.

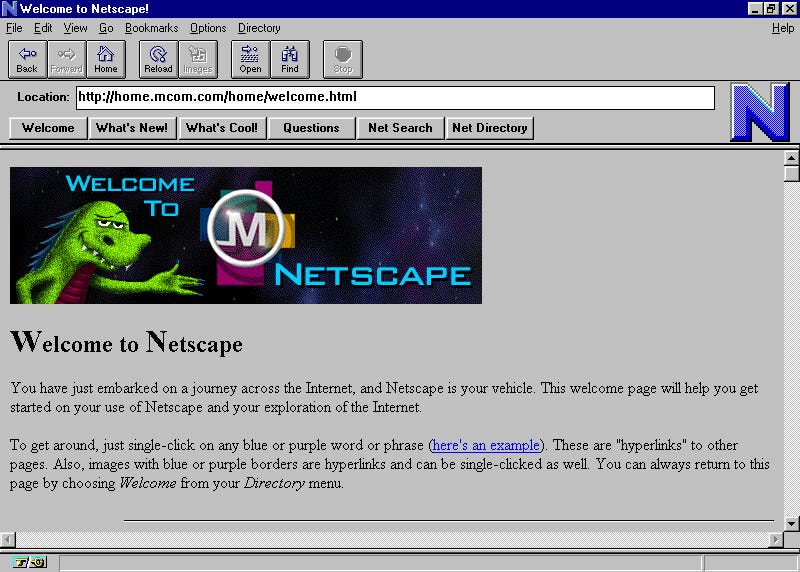

In 1994, it was becoming drastically more accessible. Yahoo! was launched, Mosaic introduced a web browser that allowed images (it would become Netscape Navigator). Most internet users accessed it by paying for America Online (AOL) or Compuserve. If you are old enough to remember the sound of dial up internet, you’ll never forget it. 1994 was also the year the World Wide Web was launched. That meant you could access the internet without paying for a special service to do so. Provided, of course, that you had a personal computer, modem, and phone line.

Although the Mariners were majority owned by Nintendo, minority owners included Microsoft executives. The idea of launching a presence in cyberspace was already on the table when the team was approached by a local internet services company, Semaphore Corporation. The Clinton White House was on the World Wide Web, why not the Mariners? Work began and the site was soft launched in the middle of November as page on Semaphore’s website to see how it behaved and worked. After testing and troubleshooting, it officially joined the information superhighway at http://www.mariners.org.

The site had a few categories: News Center for press releases and game recaps, Game Center for schedule and ticket information, Team Center for rosters and player biographies, Administration for a Mariners staff directory including electronic mail addresses for club executives, Merchandise to show off photos of novelties and apparel, and Sponsors to advertise for the companies that helped build the website.

The site was no small investment. Outside of development, it was expected to cost between $20,000 and $40,000 to run in the first year alone.1 The hope was that being able to sell merchandise and tickets, and by offering advertising, the site would pay for itself and turn a profit.

As the internet brought in more users, there was some confusion about how to navigate it. As intuitive as using a computer is for kids born after this technology boom, it wasn’t immediately clear to most adults. There were many articles in newspapers and magazines explaining what the internet is and how to use it.2

In all the newspaper articles gushing about the launch of the Mariners Home Plate, there was always some sort of explainer. “It’s on the World Wide Web, the part of the Net that requires a "browser” program like Lynx (text-only) or Mosaic (for full multimedia access)” the Seattle Times patiently instructed.3 The Times elaborated in another article, “Users can point and click with a mouse to view photos and graphics, or if they have sound cards in their computers, they can hear audio of Mariner broadcaster Dave Niehaus calling big plays from games.”4

The team was obviously brimming with excitement about the launch of the site and had big plans for the future. One idea was to assign email addresses to the players and list them on the website. That way “fans can communicate directly with their favorite star.”5 Seems like a great idea, what could go wrong?

The team was also interested in selling tickets and merchandise through the site, but acknowledged there were security concerns with having credit card numbers entered online. For the time being, they had order forms on the website that could be printed out and mailed or faxed to the club. That sort of arrangement feels clunky now, but it was a huge advancement over needing to physically go to a box office to buy tickets or needing to call and order them over the phone.

They planned to add video highlights of big games in club history (in November 1994, that would mean about two and a half video highlights, plus the cat incident). They were already looking forward to adding more. “If the Mariner home page becomes popular enough, the club ultimately would like to provide immediate inning-by-inning progress reports, with video highlight clips and sound bites.”6

MLB was carefully watching how the Mariners’ website performed. The Mariners were breaking new ground and no one was entirely sure what the new rules were. MLB was fine with the Mariners sharing basic information, but worried that sharing broadcast clips would violate broadcasting rights or infringe on the area rights of other teams. But there was no certainty on this because using game footage online wasn’t addressed at all in broadcast contracts. Until this point, MLB hadn’t even considered it. “A lot of baseball (policies) are from the turn of the century, the 1920s, if we’re generous. Nothing’s changed. This is really beyond the scope of what they’ve been dealing with,” said Kevin Mason, Mariner financial analyst and head of the Internet project.7

One article mentioned that New York Yankees owner George Steinbrenner had called MLB offices to complain about the Mariners’ web presence. Apparently he was concerned they would have some sort of unfair advantage.8 What exactly that was is unclear, but they did knock the Yankees out of the playoffs the following October, so maybe George was on to something.

Because widespread use of the internet was so new and nobody knew the rules, entities could get territorial with the information they were putting online. Such was the case when the Mariners new website butted up against an existing fan group.

Before the World Wide Web, Mariner fans could find each other and join email lists to discuss the team and games. One email list was sent a letter from Semaphore while the new website was being tested. The email list had a document online that contained information about the team. The letter informed them that the club would be taking the document under review because they wanted to make sure the any online information was “the most accurate information.”

I’m not sure what happened with that situation, but as we all know now, you can say anything you want about the Mariners online and they can’t do anything to you. That same email list popped up in the news again, a little less than a year later. While the Mariners were making their magical run through the 1995 postseason, the email list was following along. Members came from all over the country; participants described hauling their friends and coworkers in Michigan, Colorado, and New Jersey onto the Mariners bandwagon. Others said the list was helpful when they were surrounded by Yankee fans. And it was a way to stay connected, for fans living as far away as Latvia.

The Seattle Times described it as “the cyberspace equivalent of a Seattle sports bar. It's a forum where fans can question, vent, cheer, argue, strategize, dissect box scores and pick up news of the stadium-financing proposal.”9

Much like the social media networks that would come later.

*****

The Mariners were the first, but eventually every major league team followed. For a while teams ran their own websites independently. Some teams had incredible websites with a vast amount of information. Others were little more than an obligatory space holder. Then MLB standardized them and made them all bad.

I haven’t been able to find any screenshots of the original Home Plate website; the earliest versions on the Wayback Machine are from 1997. I’m not sure that I ever saw the very first version, but I do distinctly remember looking at the site in the mid-90s, before it was redesigned into the 1997 version. It had one of those tiled backgrounds and everything was centered. The sections were in little blocks that you clicked on. I wish I could find a picture because those mid-1990s website certainly were a Look.

Around the time the Mariner’s website first launched, people were so excited about the possibilities of the internet. I remember my dad talking enthusiastically about some article he read, about how the internet was going to free up so much of our time. As you read this, I’m sure you’re basking in all the free time the internet has given you.

Isn’t it ironic that the internet not only hasn’t saved us time, but has also wasted a lot of our time? At least we can all still work if we ever get nuked. And, look up the latest Mariners news. Work-life balance is important, after all.

Next Up:

Internet Fandom and the Seattle Mariners, Part 2: Netcasts and Newsgroups

Welcome back to my series on the ways Mariner fandom drove and was influenced by the development of the internet. In Part 1, we learned the Mariners were the first professional sports team to have a website on the World Wide Web:

Your Moment of Zen, An Almost Ten

To take your mind of the threat of nuclear annihilation, a couple Sundays ago AAI Award-Nominated (Heisman of college gymnastics) Skylar Killough-Wilhelm of the University of Washington was so close to scoring a perfect 10 on bars:

She scored a 9.975, which means one judge gave her a 10 and the other gave her a 9.95, probably because they were thinking, “A 10 for an unranked team? Is that allowed?” (Editor’s note: I thought you decided you weren’t going to complain about scoring this year? Me: It’s totally different when it’s not the SEC or UCLA.)

My favorite part of the routine is her piked jaeger. It is so beautiful and precise, I just want to watch it on a loop forever and ever.

FARREY, TOM. "M'S FIND HOME ON INTERNET." THE SEATTLE TIMES, November 30, 1994: C1.

I’ll be honest, here in the footnotes, I still don’t really get what the internet is. It’s like the stock market, you can explain it all you want and I can repeat those words back to you, but do I understand them? Not at all.

LLANOS, MIGUEL. "MARINERS NOT A HIT WITH ALL OF THE TEAM'S ONLINE FANS." THE SEATTLE TIMES, November 20, 1994: J2.

FARREY, TOM. "M'S FIND HOME ON INTERNET." THE SEATTLE TIMES, November 30, 1994: C1.

FARREY, TOM. "M'S FIND HOME ON INTERNET." THE SEATTLE TIMES, November 30, 1994:

FARREY, TOM. "M'S FIND HOME ON INTERNET." THE SEATTLE TIMES, November 30, 1994: C1.

FARREY, TOM. "MARINERS BOLDLY GO WHERE NO TEAM HAS GONE BEFORE WHERE CHALK LINES END AND FIBER OPTICS BEGIN, WHERE WEB HAS NOTHING TO DO WITH THE LEATHER REALITY OF A BASEBALL GLOVE, THE MARINERS EXPLORE A NEW FRONTIER." THE SEATTLE TIMES, December 1, 1994: D1.

FARREY, TOM. "MARINERS BOLDLY GO WHERE NO TEAM HAS GONE BEFOREWHERE CHALK LINES END AND FIBER OPTICS BEGIN, WHERE WEB HAS NOTHING TO DO WITH THE LEATHER REALITY OF A BASEBALL GLOVE, THE MARINERS EXPLORE A NEW FRONTIER." THE SEATTLE TIMES, December 1, 1994: D1.

PRYNE, ERIC. "INTERNET PLUGS IN M'S FANS." THE SEATTLE TIMES, October 14, 1995: B9

I remember that when MLB required all teams to use their template for their web presence, it seemed like a giant step back from what the M's were doing at the time.

The cat video 🤣🤣🤣🤣🤣